I recently had the opportunity to tune an 1888 Vose & Sons upright. Its amazing to play an instrument that has so much history! My Great-Great-Grandmother could have played this instrument! This particular piano was shipped around the horn of South America (before the Panama Canal) and sold from San Francisco in the late 1880’s.

As interesting as old pianos are, there are plenty of tricks and risks when working with them. Most pianos made before 1900 weren’t actually designed to be tuned to our modern A440 standard of pitch. The combined high tension of 200 strings on a modern piano creates about 40,000lbs of pressure on the iron plate. Smaller, lighter metal plates and weaker (and often corroded) strings on old pianos often can’t hold up to that kind of tension. They weren’t created to withstand that amount, and they have over 100 years of wear on the original materials.

So when I start to tune an antique piano, I have to decide where to tune it. First I will check to see if there are any missing or replaced strings which would indicate a history of strings breaking. Then I will measure the pitches of several notes through the piano to find out approximately where the piano’s string tension currently is. If all looks good, no broken or replaced and no or minimal corrosion on the strings, and it is fairly close to pitch, I will carefully tune it to our modern A440. That way the piano can be played with other instruments and it helps the player develop a good sense of modern pitch. If there are broken, replaced or corroded strings, I will usually tune the piano to a lower standard, usually (but sometimes a good deal lower) A435 or A432.

Deciding what pitch standard to use is the most stressful and dangerous part of working with older pianos. If I choose incorrectly, strings could break which mean costly repairs and several return visits to tune brand new strings which go out of tune constantly while the new piano wire continues to stretch over 1-2 years.

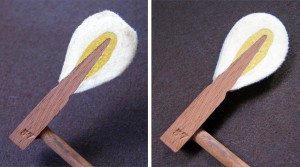

Old pianos also have odd and non-standard parts which are often brittle and fragile with age. So not only do they break easily, but they are hard to replace or reproduce.

This well-built 1888 Vose & Sons had some replaced strings and was a good bit lower than A440. I chose A435 as a good place to tune and it sounded great when I was finished. I eased a couple tight parts to help the action move faster, and everything responded well to my work. The piano sounded and played much better when I was done! The owner was happy and I was satisfied in “doing no harm” and keeping a beautiful old piano working well for its owners.